The K-shaped society

Back

This piece was originally published on the Laura's blog here.

One of the worrying things about post-pandemic life is that it might be K shaped.

Economists are already talking about the ‘K-shaped’ recovery. In a normal economic shock, everything goes badly for a bit (\) and then it goes back up again (/). Hence there is a \/ shaped recovery.

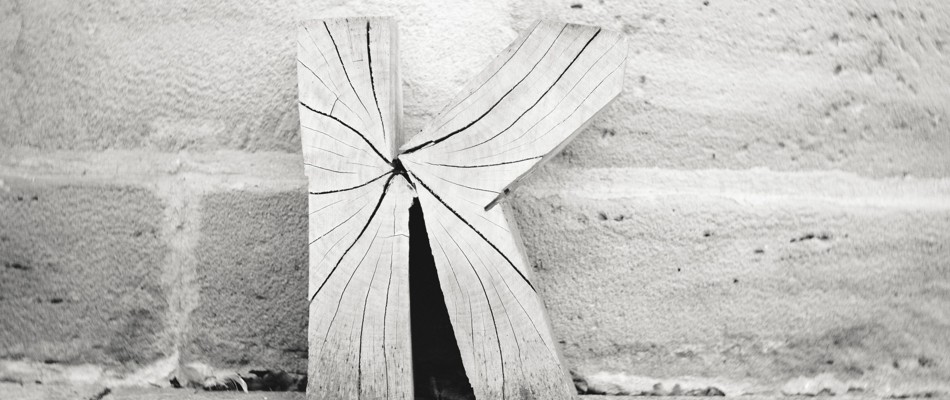

In this pandemic, however, business activity has looked more like this, with some businesses suddenly growing lots while other shrink:

Why has this happened? Some businesses have really benefitted from the pandemic. Amazon, Zoom, face mask manufacturers, people who sell vaccine supplies. Their businesses are booming. They are the top line of the K.

Meanwhile, anyone running a nightclub, airline or hotel is likely having a nightmare. Today I learned of a company that runs 144 tuition centres, mainly in supermarkets, across the UK. They’ve lost £10m and fired 20% of staff. Many centres will never re-open. They are bottom line K.

But it’s about more than business

What happens to businesses also happens to families. The fired staff in that tuition centre are now scrambling for a job, along with a predicted 2 million other people by the end of this year. Those who haven’t lost jobs, but have been furloughed, will have been running on 80% wages for a while, and still don’t know if they have certainty for their future. Mortgage holidays are racking up. Landlords may need to start selling houses due to lost payments. There is a great deal of uncertainty.

BUT, not everyone is in this situation. At the other end of the scale there are families where all workers have kept going – particularly those in public services. Wages are not necessarily high, but they’re often higher than median salaries in the private sector, and there are good pension benefits.

Families who have kept earning have mainly reduced their spending. After all, what can it be spent on in a pandemic? Cancelled holidays, little eating out, commuting costs much reduced for those at home.

Hence, family life is are also likely to be k-shaped too.

What does this mean for schools?

Children typically live inside families. So their lives are likely to be affected in K-shape ways too. Those children in more unstable families may feel less secure and have fewer facilities for learning – laptops, wifi, a space of their own in which to study.

However, there’s another factor at play for children too. Some children simply learn better with fewer distractions, going at their own pace, and in the relatively safe surroundings of their own home. I’m not going to suggest that it’s many children who are like this. The peer effects of school, and the social pressure of seeing other children learning, are not to be under-estimated. But there are children for whom the pressures of being in school, every day, in a large class, with lots of different children vying for teacher attention all at once, is difficult.

I’ve lost count of the number of parents who have tweeted or messaged me to say their child is loving being at home and has been more productive because of it. “He’s much happier sending the teacher a message to ask for help rather than putting his hand up to ask in front of everyone”. Being real, aren’t we all better at that?

Children have also had different access to learning throughout the pandemic. Last year, private schools were very quickly able to transfer to online learning, with an emphasis on live-streamed lessons. For a myriad of reasons, state schools took longer to get to the same position. While private schools marched ahead, there’s no doubt that many more state school pupils had less time and less effective learning than their private school peers. (To be fair, this is precisely the advantage that parents who send their children to private school pay for, but the state does a fairly good job most of the time of clawing it back. Last year, they simply weren’t in a position to quickly do so).

Hence, children are also facing a k-shaped future:

What does this, or should this, mean for schools policy?

All of the above is uncalculated. I don’t know exactly how big these differences are. But they strike me as compounding forces. The child who gets an extra six months of learning at age 12, will get further and further ahead compared to the child who got behind and is now forever ‘catching up’. Hence, what begins as a small ‘k’ soon becomes a very big ‘K’ and so the gap continues widening.

As I see it there are two strategies for reducing the ‘Expanding K’ problem and I suspect the two political parties are likely to go for different ones.

My guess is the Conservatives will stick with their focus on ‘levelling up’. That is, try to bend the bottom line of the K up towards the top.

They will do it by focusing on making things ‘better’ for those on the downward trajectory. Obvious policies include vouchers for catch-up tuition, opening more free schools/academies in areas with lots of schools with weak Ofsted grades, and maybe something around ‘admissions’ at top universities (maybe tuition fee waivers for top A level scorers in schools in the bottom deprivation quintile, that kind of thing).

Labour, meanwhile, I think will attempt a ‘squeeze’ strategy. That is, try and slow the growth of the top line as well as bend upwards the bottom line.

How Labour can do this is less obvious. My oblique solution is that to help the lower K line, Labour would be better off focusing on other public policies – welfare, safeguarding, youth justice, food, housing, and so on. Reform those and schools will likely gain more capacity to solve their issues. Reducing the top line is politically difficult, but some ideas could be putting more burdens on private schools (eg removing VAT exemptions) and/or putting quotas on university entrance. If they’re feeling particularly brave Fiona Millar’s suggestion of refusing to provide grammar schools with grants for school buildings/improvements unless they become comprehensives will also have merit.

The limits of these approaches

Both of these approaches have limits.

For the Conservatives, their policies equal a decent ‘retail’ offer. By which I mean it’s easy to sell at an election in 2024. There is something instinctively positive about the idea that those who are succeeding should be left to keep flying, and those at the bottom should be given ‘a hand up’ through vouchers, more good school places and an extra boost of tuition.

The downside is that it probably won’t actually help inequality. Policies like these tend to help those already doing okay as they favour the already-bright and/or get vultured by the middle classes. (If we give free tuition to top A-level scorers in the state sector, we can expect an influx of middle class kids into state sixth forms in Year 13!)

For Labour, the problem is that it’s hard to get people to vote for policies if it means holding some people back. Also, while other public policy reforms will help schools, there will still need to be a ‘school’ narrative to hold its own against the Conservative one. ‘We are improving social work’ won’t placate most people on the doorstep. Hence, there will need to be some quite specific offers to parents – but it would be smart not to make these too onerous or overly crazy. Getting control over class size is a good one (especially as it’s relatively easy given the birth rate has gone down quite a lot!) also something about making teachers better qualified. (It’s worth remembering that free schools and academies are allowed to employ unqualified teachers – that would be easy pickings).

Both parties also ought to think about ‘life long learning’. Some of the most difficult, but important, education policies enable people who find themselves on a downward k-line to switch to the top k-line. The Conservatives have signalled they’re looking at this in the new FE White Paper – with policies such as lifelong learning loans and 400 free courses for anyone without a level 3 qualification. In the last election, Labour came up with a ‘National Education Service’ which could do something similar.

And what about on the ground?

On the ground, in actual schools, all of this looks much the same as it ever did. Schools have always dealt with the fact that some kids turn up on a trajectory of life that seems to spiral interminably upwards, and others are running for a bit to catch up but seem stubbornly caught in a downward spiral.

All the usual applies: keep improving teaching, keep observing learners closely and intervening as needed, keep looking for the wider opportunities to keep kids motivated, behaving, and learning stuff. The world can be U-shaped, K-shaped, or like one of those massive German letters (ß), it doesn’t matter. Good teaching is still good teaching. Stick to that and all will be well.

But beware the K. It may loom larger than we expect.

Laura McInerney is an education journalist and speaker, co-founder of the daily survey app Teacher Tapp, and a former teacher.