Why is a baccalaureate the way forward?

Back

This chapter first appeared in SFCA's collection of essays and case studies, Sixth Form Matters, and is re-posted here to reach an audience who may not have read the original book.

Our education system has many strengths. We have fantastic teachers, innovative leaders, and wonderful schools and colleges that are continuing to improve year on year. The last ten years have seen an increasingly dynamic community of teachers, policy researchers, and school and college leaders who are engaged with research and committed to seeking excellence and tackling disadvantage. But, despite these strengths, too many young people, especially those judged to be at the lower end of the attainment range, are denied the opportunity to leave education with a fair record of their successes and achievements, however hard they work. Too often, young people’s educational careers are defined solely in terms of exam results, often in a narrow range of disciplines and with inadequate regard for technical education, creative learning, and personal development.

The COVID shutdown provided an unsuspecting public with an insight into how these exam grades work. The number of good GCSE and A Level grades that can be awarded in any year is more or less fixed (in a process known as comparable outcomes) to reflect that cohort of pupils’ performance when they left primary school. This means that demonstrating real improvement is difficult and exam results are a zero-sum game. For some pupils and institutions to get a good pass, others must ‘fail’. The third of all pupils who leave education without the accepted markers of success often have greatly reduced life chances. Addressing this should be critical to any levelling up agenda.

Moreover, the status divide between academic and technical education that has bedevilled the English school system for generations shows no sign of going away. It is one of those big education dilemmas that tends to produce small, inadequate solutions. The 1944 tripartite settlement proposed technical schools that never happened; in the subsequent 75 years a series of technical qualifications of varying quality, and permutations of the FE sector, have come and gone as frequently as education secretaries.

Of course, level 3 technical learning, often taking place in a workshop- style environment, and vocational learning, usually in a classroom, share common characteristics, including a close relationship between learning and its application in the workplace. But there are significant differences: while a technical course is likely to be associated with a particular trade, perhaps a license to practise, and often entails the acquisition of ‘hard’ workplace skills, vocational programmes, notably so-called applied general qualifications such as BTECs, are more closely aligned to an academic curriculum, with, more commonly, a focus on the acquisition of soft skills and progression to university and professional careers –and have proved to have more sticking power, perhaps due to their proximity to ‘academic’ courses.

Sir Mike Tomlinson’s review of 14–19 education resulted in a serious proposal for a wraparound qualification at 18 that would include both vocational and academic pathways and attempt to overcome the parity of esteem issue. Unfortunately, it was swatted away by Tony Blair’s government as a threat to the A Level ‘gold standard’. The last Labour government’s diplomas were short-lived. The Wolf review suggested that lower-quality technical qualifications should be removed from performance tables and potentially abolished completely. This led to the reform of applied general and technical qualifications to fit the new ‘RQF’ framework in 2016 and contributed to the level 3 review, which is still ongoing, leaving a question mark over some of the most popular awards such as BTECs, while promoting the introduction of T Levels, on which the jury is still out. Meanwhile, the economy is in a more perilous state, we are facing a skills shortage because of Brexit, and the frailty and unfairness of the accountability system was brutally exposed during the two years when there were no externally marked exams to prop it up.

Why is a baccalaureate qualification the answer? Very few other countries have a system quite like ours in which young people are obliged to take so many exams at 16 and 18, as well as being forced to specialise by choosing a few subjects for A Level when they may only be 15. A more common option is some sort of diploma or baccalaureate qualification at 18 which, as Sunak proposes, also involves studying maths and the native language to 18. This type of end of school ‘umbrella’ award can also encompass a wider range of non-academic achievement and, with imagination, we could establish something similar here.

Imagine a qualification that would allow the most able students depth and breadth across several subjects, while including young people who might otherwise be ‘left behind’. This qualification could include exam results, vocational awards, as well as accomplishments in the creative arts, sport, project work and civic activity, and permit every pupil to achieve at some level. This wouldn’t just broaden the definition of what we mean by a ‘good education’, it would also help to minimise the status divide between academic and technical routes by unifying them under one award. It would be internationally comparable with other baccalaureate qualifications that blend academic and technical learning with personal development, and it would mean we could finally talk about young people’s achievement in more than just binary pass/fail terms.

At the National Baccalaureate Trust, of which we are both members, we have been working on detailed proposals about how a home- grown baccalaureate might work. In practice we recognise that getting a new qualification off the ground requires investment, including addressing the disparities in the way funding works between pre- and post-16 providers. It would also take a good deal of consultation and preparatory work, cross-party support, and a 5–10-year implementation cycle. To give our ideas a push we have developed an interim model and we are trialling our ideas in some schools. We are now keen to find others who might want to join this process, not least because real life examples of a baccalaureate in action could show policy makers how the transition could happen relatively smoothly, using the strengths of current provision and incorporating existing qualifications that are familiar to students and parents in a framework that is more holistic and integrated than is currently the case.

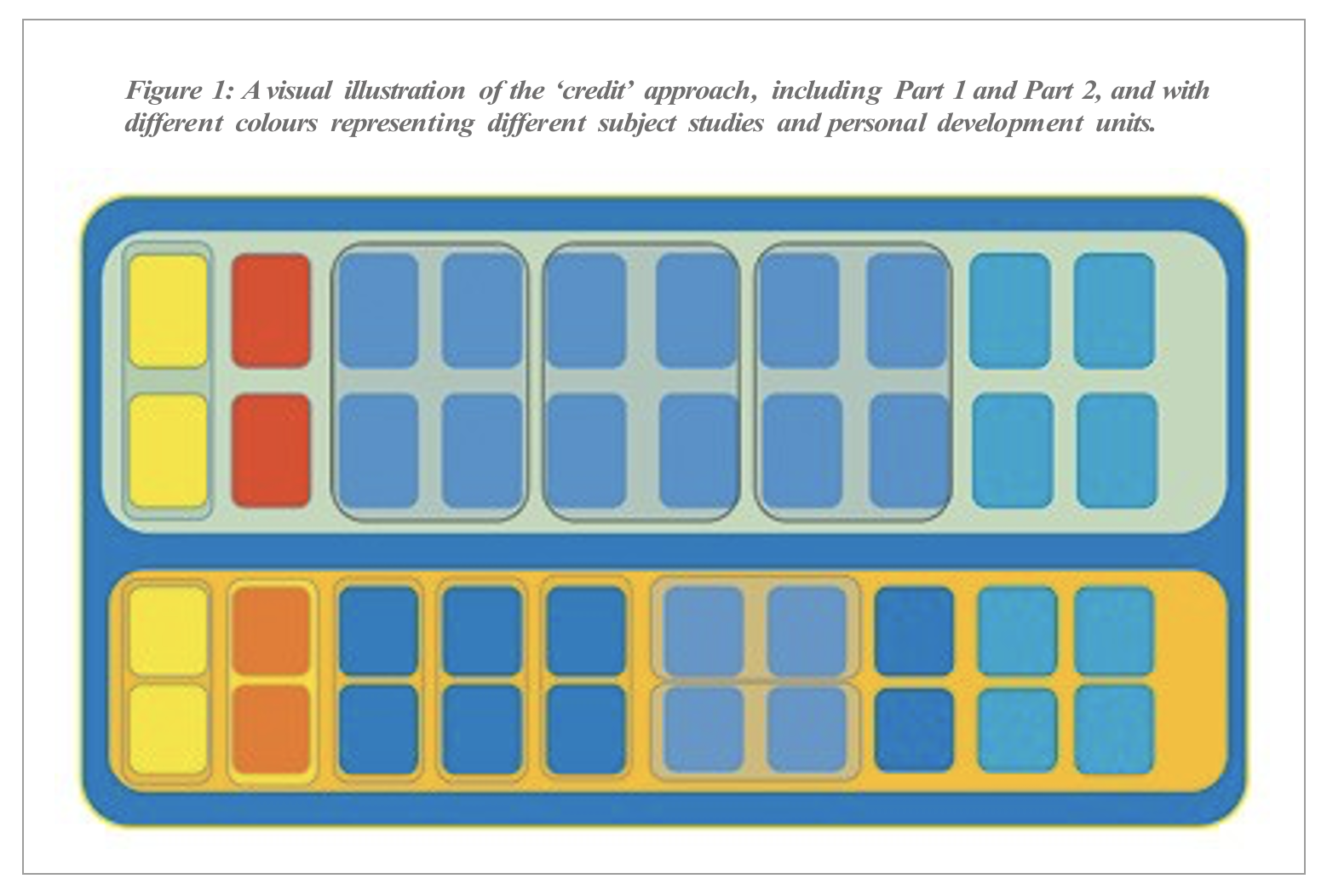

We have a few red lines for what you might describe as our ‘final product’. A national baccalaureate must be universal for all 14–18-year- olds, with embedded levels of achievement in a common framework. In practice this means entry level, foundation, intermediate and advanced awards. It should be deliverable in existing institutions, with 11–16 schools, sixth form colleges, and FE collegesplaying their part alongside 11–18 schools. This means that students should be able to complete a Part 1 in Year 10 and 11 in 11–16 schools and a Part 2 in colleges, or both parts in an 11–18 school.

Our baccalaureate would have two components – core learning and personal development. Students would select a combination of subject units broadly equivalent to our GCSEs, A Levels, T Levels, and other vocational and technical qualifications. We suggest that the current volume of existing qualifications be reduced, allowing students to explore a wider range of subjects and personal development units that would not be examined and keeping the scale of the examined components in proportion. These units would form a wider portfolio rather than act as stand-alone qualifications, but each element of the baccalaureate would be given a credit weighting indicating the volume of the curriculum it represents, enabling students to pursue different pathways of broadly equivalent value within the existing system of levels. Like Sunak, we propose that students should continue to study maths and English to 18.

The second component would comprise credits in a range of personal development areas which all students would complete. These should include an independent extended project and a minimum of ten credits in each of the following areas: physical or outdoor education, the creative arts, community service, work experience, and leadership and mentoring. Assessment of all the component parts would be either by examination, coursework, or centre assessment with moderation, depending on the subject discipline, and could involve established external providers – such as the Duke of Edinburgh Award or National Citizen Service schemes.

A minimum number of credits would be needed to complete the overall baccalaureate award. For illustrative purposes we have suggested Part 1 has 200 credits and Part 2 has 400 credits – so the maximum final score at 18 would be 600 points. Each completed award would be accompanied by a full digital transcript detailing the student’s achievements in the component elements in a common format which would allow young people to transfer between institutions between Part One and Part Two, passporting their achievements so that they can continue to work towards the full National Baccalaureate. This would address a legitimate concern that this type of approach would not work within the English education system when so many young people move between providers at 16.

There will of course be many arguments against this type of reform, and no doubt they will be aired if the Sunak proposals get off the ground, or the Labour Party decides to do something similar. The first is that focusing on a final award at 18 would inevitably lead to abolishing GCSEs. We hope we have explained why our model doesn’t leadinevitably to that conclusion. Our approach would be to build the baccalaureate around existing qualifications like GCSEs in the first instance, to build confidence and ease the transition. Ultimately, once the final award gains acceptance, the need for separate contributing qualifications would be unnecessary and we could remove GCSEs as stand-alone qualifications. The GCSE, and before it the O Level and CSE, were established when the school leaving age was 16. Over time it may become hard to justify so many high-stakes tests when all young people are obliged to stay in education and training for anothor two years.

The next claim is that this type of award, in which everyone can experience success, would be a more woolly, less rigorous qualification than we have now. For some of today’s purist educationalists, anything that doesn’t allow a significant proportion of youngsters to fail, or dares to celebrate personal development, the arts, culture, creativity, and skills, constitutes a ‘dumbed down education’ – which is strange, because parents pay a fortune for exactly those opportunities in the private sector. No one accuses the International Baccalaureate of being a woolly qualification lacking in rigour. In fact, it really is an international gold standard, celebrated across the globe for its promise to develop ‘a broad range of human capacities’ and requiring pupils to complete projects in creativity, activity and public service as well as achieving academic success.

At the same time as the critics, there are also powerful advocates for this type of reform in England. Education minister and former chair of the Education Select Committee Robert Halfon has proposed abolishing GCSEs altogether and replacing them with a baccalaureate qualification at 18. The Conservative One Nation Group also supports the baccalaureate idea and believes it would contribute to the government’s ‘levelling up’ agenda. Former Downing Street adviser Peter Hyman, co-founder of the Big Education academy trust and now working for the Leader of the Opposition Keir Starmer, has called for a final pupil ‘transcript’ which would award credits for a range of projects and skills over a pupil’s entire school life.

Finally, there is the real concern that yet another huge policy upheaval in secondary education would be a difficult electoral sell to parents and teachers. No reform on this scale is easy, and schools and colleges are understandably wary of too much change at a time when they are struggling with real-terms funding cuts, a decade of previous reform, and constantly changing national leadership. There have been seven Prime Ministers and twice as many education secretaries since Sir Mike Tomlinson proposed something similar.

But this is why we are advocating a long lead time. Parents can now see, partly thanks to the pandemic disruption, that too much of their children’s education is driven by an exam juggernaut that crushes everything that might be enriching and life-enhancing in its path. This idea could be sold as a huge investment in our country and its young people at a time when they desperately need some hope. What could be more important than that?

Fiona Millar is an education journalist and campaigner who is also a secondary school governor in London. Tom Sherrington is an author, education consultant, and founding trustee of the National Baccalaureate Trust. For more information about the National Baccalaureate Trust, the proposed model, or to join the pilot scheme please visit the website, or contact natbaccforengland@gmail.com.